An extraordinary thing happened the other day. An episode of Music Inside Out reached the program’s biggest audience ever on Facebook — more than 47,000 people, who clicked nearly 8,000 “Likes.” Talk about a kick in the head.

Part of what made the result so singular is that the episode we ran was dedicated to country music, which is not as popular in New Orleans as it is in other areas of the state, or the region.

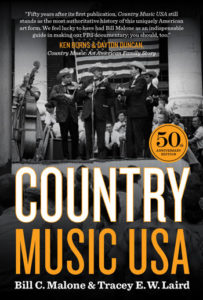

We’d interviewed historian Bill C. Malone who wrote the book on country music back in 1968, updated it in 1985 and in 2018 issued a 50th anniversary edition. Country Music, USA has never been out of print and Malone, 85, has kept his ear to the airwaves all these years, finding new angles, artists and songs to talk about. His many subsequent books and articles explore the music as well as the working class people who created it and for whom it has always meant so much.

When the Ken Burns team went looking for an expert to guide them through the history of the music, they could do no better than Malone — and didn’t. He was the resident historian of the PBS Ken Burns: Country Music series and when he wasn’t on camera, the narrator Peter Coyote was repeating ideas that Malone had formulated originally in print so long ago.

The Singing Historian

What makes Malone compelling as a retired university professor, author and songcatcher, is that he sings. At Tulane University, where he spent 25 years in the classroom, he would bring his guitar to class and perform some of the most cherished songs in the country music canon — standards by Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams, the Carter Family and more.

But for a man who sang repeatedly to a captive audience of students, he was no ham. Before anyone would think to applaud, he’d be talking about the particulars of the songwriter, the performer, the listening audience, the radio station. He knew that hearing the song sung simply and in real time had the potential to move students emotionally, pique their interest and help them better understand why the music matters. During our interview he did something similar. Malone, singing a capella, conjured a song that his mother sang on their cotton farm in East Texas and I just about cried.

When the world from you withholds

Leave it There, written by Charles Tindley

Of its silver and its gold

And you’ve got to get along on meager fare

Just remember in His word

How He fed the little bird

Take your burden to the Lord and leave it there

Leave it there, Oh, leave it there

Take your burden to the Lord and leave it there

If you trust and never doubt

He will surely bring you out

Take your burden to the Lord and leave it there.

“I didn’t learn until many years later that was written by an African-American composer named Charles Tindley who had a church in Philadelphia at the early years of the 20th century,” Malone said quickly. “And he wrote a lot of songs that moved beyond his church out in the hinterland and became the possession of white and black people. I think anyone who was poor and isolated and suffering could find release in that song.”

Can you imagine what his classes were like?

For that afternoon, I felt as if I were back at school, except this time I could ask more questions and there was no grade to worry over. Many of our local listeners must have felt that way also.

World Music

And yet, the most surprising thing about the listening audience that week, according to Facebook, is that the overwhelming majority of people who heard or showed interest in the program were in Kenya. East Africa has a long history of country music fandom. Radio stations across Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan spin country favorites every day on the radio, or people play the songs on their own devices. I wrote a story saying as much from Nairobi in 2007.

“kenya 97” by Mister_Jack is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

So it came as a pleasant surprise that all these years later, Kenyan listeners — many of them young — are still as eager to hear country music. As I recall, they were particularly enamored with Jimmie Rodgers, Jim Reeves, and Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton singing separately or as a duo. On a six-hour drive from Northern Uganda to the capital city of Kampala, I remember hearing “A Coat of Many Colors” more than dozen times.

Back through the years

I go wonderin’ once again

Back to the seasons of my youth

I recall a box of rags that someone gave us

And how momma put the rags to use …

— Coat of Many Colors, written by Dolly Parton

In Nairobi, the songs of Kenny Rogers, who died this month in Sandy Springs, Georgia, meant a great deal to radio listeners. No one there, or anywhere, could deny the power of his storytelling and he had just the right material: “The Gambler,” “Ruby Don’t Take Your Love to Town,” and, in particular, “Coward of the County,” in which the hero, a lifelong pacifist, fights the “Gatlin boys” who had raped his sweetheart.

Twenty years of crawling was bottled up inside him

He wasn’t holding nothing back, he let ‘em have it all

When Tommy left the barroom, not a Gatlin boy was standing

He said, “This one’s for Becky,” as he watched the last one fall

— Coward of the County, written by Roger Dale Bowling and Billy “Edd” Wheeler

Turn Your Radio On

Country music — and particularly the old songs — can keep you company like almost no other popular music. The stories are often unforgettable and they unfold like morality plays, continuing the oral traditions that originally grew out of rural communities across the United States. And, as Malone stresses in our interview, the music has always been the expression of black and white people from those communities and others. That’s why country music appeals to people in Africa and around the planet, including listeners of Music Inside Out.

On the last day that I saw my friends Nadine and Simon Blake, I played that part of the Malone interview in which he sings the hymn, “Leave It There.” It ended the dinner before we self-isolated against the spread of the novel coronavirus. Turns out, that song has a kind of universal power that may transcend religiosity. It expiates worried feelings and gives calm and hope in return. Dang, that Malone is good.