A Voice For The Trumpet

Terence Blanchard’s Gift For Making Music

When the microphone switches on, some people freeze. They can’t think of a thing to say. But Terence Blanchard relaxes.

Blanchard does some of his best thinking in front of a microphone and he’s impatient to get his ideas recorded. That might explain why he is so prolific and why he is so good.

Terence Blanchard is a multi-Grammy winning trumpeter and composer. He is comfortable in jazz and orchestral music, as a side man or as the main attraction. He also shines playing bossa nova, mambos and gospel. Blanchard has released dozens of albums and appeared on more than fifty movie soundtracks.

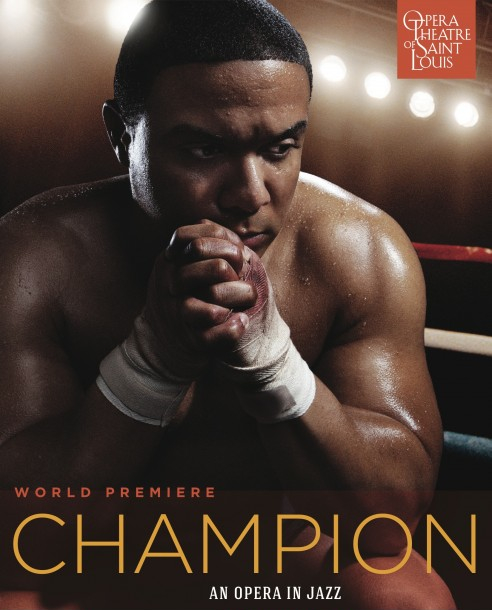

When we spoke, in 2013, he’d released a CD of original music, called Magnetic (which earned him a 2014 Grammy nod.) And just a few weeks later, Opera Theater of St. Louis unveiled Terence Blanchard’s first opera in jazz, “Champion.” Since that time there’ve been more albums and still more awards, including a 2019 Best Instrumental Composition Grammy for Blut Und Boden (Blood And Soil).

Connect with Terence Blanchard — Twitter | Facebook | Website | iTunes | IMDb

Lionel Hampton

Blanchard grew up in New Orleans and went to college at Rutgers. As a freshman, he met the great vibraphonist Lionel Hampton.

“I stayed with the guy who was running the jazz department at the time,” Blanchard says. “His name was Paul Jeffrey. And Paul was playing with Lionel Hampton. So, he was going up to do a gig with Hampton and he said, ‘Hey man, just bring your horn.’

And it was there, hanging with the guys in the band, that Blanchard met Hampton.

“He rolls up behind me and he says, ‘Hey Champ, let me hear you play blues with the piano player.’ And I go, ‘Okay.’ So I started playing the blues and he says, ‘Man, I’m going to hire you. I want you to join the band.’ So the next week I was going on the road.”

That experience with the great band leader got folded into Blanchard’s college education.

“I had this creative writing class, you know Monday morning, that I would skip every now and then but the guy who ran the class was really cool. He was a big jazz fan. He knew what I was doing so he made me write papers about my experiences.”

Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers

The 19 year-old Terence Blanchard was caught in a whirlwind. The experience with Lionel Hampton was only the beginning.

Blanchard tells Gwen Thompkins, “I go from being in New Orleans, then playing with Lionel Hampton, then being in Europe with Art Blakey, and meeting Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie. I already knew Clark Terry from here. Freddie Hubbard. All of these people. Eddie Lockjaw Davis, Jimmy Heath, James Moody… these are all the musicians that I was meeting.”

The magnitude of the experience didn’t sink in at first.

“It took years for me to sit back and realize, ‘Well, wait a minute, man. I had an amazing entry into this business by meeting all of these people.’ Not only meeting them, but having them take an interest in you and wanting to talk to you.”

That was especially the case with Art Blakey.

“When I first joined the band, the first thing he said to me, he said, ‘Listen, you are in this band to learn how to become a band leader.’ He said, ‘I don’t want you to leave this band and join anybody else’s band.’ He said, ‘We are trying develop band leaders to have this music grow.’

Blanchard remembers Blakey saying “That is my mission in life.”

In fact, Blanchard says, Blakey used to joke about his mission: “He would say, ‘I stick with young people. When these get too old I’m going to get me some younger ones.’”

Growing Up in Ponchartrain Park

The Pontchartrain Park neighborhood of New Orleans is billed as the first neighborhood built for middle-class black residents in the United States.

Planned in the 1950s and built around a golf course designed by Joseph Bartholomew, with houses largely financed by the G.I. Bill, it was home to longshoremen, postal workers, brick layers, teachers and watchful mothers.

“I remember one time when I was a little kid I was trying to smoke,” Blanchard remembers. “I thought I was going to be cool. I was walking down Press Drive and I saw somebody else’s mom and just totally freaked and went, ‘Oh my god.’

And I think about how great that was that everybody was so involved in everybody else’s kids’ lives. And when you talk about ‘It takes a village,’ we grew up in that village.”

Blanchard credits his father, an insurance salesman by day and a hospital orderly by night, for instilling in him a love of music, including opera.

TB Carmen. Definitely.

GT Bizet.

TB Oh yeah. Definitely. That was probably one of the most played recordings in the house. And I remember dad had those old RCA Victor recordings.

GT Yes, the heavy ones!

TB Yes, exactly, that we weren’t allowed to touch.

GT No, yeah.

TB I mean it is kind of interesting. I’ve worked in the world of opera now, but back then I remember my dad would put on these records man and you’d hear door slamming in the house.

GT Nobody wanted to hear it?

TB Yeah. Everybody was like, “There he goes. Boom.” It was pretty funny.

It would not be the last opera experience for Terence Blanchard.

Champion: An Opera in Jazz

The story of Emile Griffith turns on a fight — a terrible, terrible fight. But which fight?

In 1962, Griffith met Benny Paret in the ring at Madison Square Garden. Griffith beat Paret so badly that Paret fell into a coma and died ten days later.

At the time and throughout his entire career, Griffith also battled his sexuality. Griffith’s bisexuality was reportedly an open secret in the boxing world. But at the weigh-in before their fight, Paret mocked Griffith publicly, calling Griffith a Spanish vulgarism for homosexual.

“I kill a man and most people understand and forgive me. However, I love a man, and to many people this is an unforgivable sin; this makes me an evil person.”

Nine Ten and Out! The Two Worlds of Emile Griffith

Blanchard, an amateur boxer, chose the Emile Grififth story as the subject of his first opera. He wrote the music and Michael Cristofer — the Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright — wrote the libretto.

Opera Theater of Saint Louis mounted the world premiere of “Champion” in the summer of 2013. Many in the audience loved it.

Preview of Coming Attractions: Blanchard Film Scores

Terence Blanchard’s music has appeared on the soundtracks of more than 50 films and TV movies, from “Malcolm X” to “Mo’ Better Blues” to “Clockers” to “Jungle Fever.” You can see the complete list here.

“Well generally what you first try to do is watch the entire film and say what does the film need and what does the film call for?

“It is a combination of things because the chords can be colors but also the orchestration can be. The chords will give you the general sense of certain types of emotion, but the orchestration can tell you how deep you are gong to delve into that emotion.”

Terence Blanchard

When we decided to do an entire program on movie scores and soundtracks, it made perfect sense to invite Blanchard back to talk some more about this demanding art form. Here’s that conversation:

Terence Blanchard Playlist

Terence Blanchard was nominated for a 2014 Grammy Award for “Don’t Run” from his album Magnetic. You can listen to it here:

We’ve put together the complete playlist of the music heard in this hour which you can read online or download to take with you to your local record store. Many of the cuts are available for you to stream to your desktop or mobile device. Enjoy exploring Blanchard’s music.

Excerpts from the performance of “Champion” heard on Music Inside Out were provided by Opera Theater of Saint Louis with the permission of the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra.