Wendell Brunious

Follow the Leader

By his count, trumpeter Wendell Brunious knows more than 2,000 songs. Some are from the Great American Songbook, some are traditional, swing and bebop jazz gems and many are from the golden era of New Orleans rhythm and blues. A goodly few are homemade. Wendell’s father, John “Picket” Brunious, Sr. was a composer and arranger, as was his brother John, Jr. Wendell says he plays their music to keep them ever-present, but he has his own of stock of originals. Over a more than 50 year-career in the business, he says his number one rule remains, “Keep it simple, stupid.”

“It’s kind of like my golf swing,” Brunious tells Gwen.

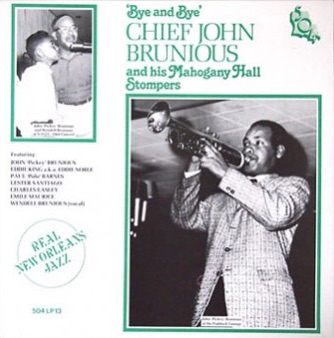

Brunious has recorded seven albums under his own name and been featured on many more. He hasn’t always lived in New Orleans, but his roots in the city’s musical tradition run deep, beginning at home with his family. Brunious couldn’t be more proud of his multi-generational, trumpet-playing clan. His father and seven of his siblings cleaved to the instrument, as did his nephew Mark Braud. Four of them have led the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, including Wendell who played at the Hall for more than 20 years.

Playing in Paragraphs

Picking up a trumpet is not like picking up any other instrument, he says, because “No matter whose name is on the contract, the trumpet player leads the band.” So how do eight leaders sound in one household? “Noisy.”

That may be why Wendell has a particular fondness for melody. “My daddy used to say, ‘If you don’t know the melody, you don’t know the song,” he said. And to the melody, a seasoned trumpet player adds economy. “You don’t have to be hitting a high note just to unnecessarily prove you can do it … you hear a lot of examples of that. You do hit high notes, but when they mean something. When I play, I try to play almost in paragraphs, to make a statement. Then my next chord is another paragraph, and so on.”

Danny Barker

The jazz guitarist and banjo player Danny Barker suggested that John Brunious, Sr. replace a young Dizzy Gillespie when he left the Cab Calloway Orchestra. Everybody won. Brunious, a Juilliard graduate, cinched a job that helped launch his career. Calloway got a trumpet player who arranged “Minnie the Moocher,” his biggest-selling recording. Gillespie went on to international stardom as a founder of bebop. And Barker — an excellent raconteur — got the bragging rights.

And yet, Barker’s greatest achievement may have been the Fairview Baptist Christian Marching Band, an incubator for young brass band talent that helped secure the New Orleans music tradition well into the 21st century. Leroy Jones, Gregg Stafford, and young Herlin Riley played trumpet, (Riley later switched to drums). Dr. Michael White played clarinet. Shannon Powell played drums. Lucien Barbarin played trombone.

An Education on Bourbon Street

Most of these musicians became band leaders and, as sidemen, have toured the world with other acts, including Harry Connick, Jr., and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. But Wendell Brunious, who describes himself as a self-taught trumpeter, didn’t join:

WB: I just didn’t. I just stayed at home and played around the house. I don’t know if I was afraid of the competition or what exactly. I’m not afraid of competition usually but I didn’t do that. I don’t know exactly why. I became friends with a lot of those guys.

GT: Exactly and you play with a lot of them to this very day. Shannon Powell and you often play together — and Herlin Riley. I’ve seen it myself. It’s wonderful. Dr. Michael White. Talk a little bit about Bourbon Street as an education. Not just people who want to see naked ladies, but an education for a musician.

WB: Well, in those days, that is 1975. Yeah. ‘Cause I turned 21 on that job there. On Bourbon Street, you’d could go and hear some top-notch musicians. Al Hirt was out there. Pete Fountain, they had a band out there. Roy Liberto and Thomas Jefferson.

GT: Right. Thomas Jefferson – he always had the greatest name, right?

WB: There are so many stories about Thomas Jefferson. But, he was a great trumpet player and a great singer. Oh my God. Few people know this, but Thomas Jefferson took a band up to St. Louis, and they called themselves the Brown Cats.

GT: The Brown Cats.

WB: Yeah, and it was Famous Lambert, Adam Lambert, from Thibodaux. Lloyd Lambert sometimes played I think the bass, Family Williams, Thomas Jefferson, Big Sam Dutre and Miles Davis used to go sit in the audience – this is up in St. Louis now – used to go sit in the audience. One time, Thomas Jefferson came home and they asked Miles to play with them. There were there those two weeks. You look in the book! Miles’ book. His autobiography. He talks about this, how he got a chance to play with those cats from New Orleans cause he was like, “Whoa, you guys got groove man.”

Music at the Pharmacy

For generations, the Circle Foods Store was an anchor for Creole families in the Seventh Ward of New Orleans. That was the place to go for seafood, bell peppers, onions, celery, butter, rice, cream and flour — staples of so many Creole specialties. When stuffed mirlitons were for dinner, or crawfish bisque, mothers sent their children to Circle to pick up the ingredients. But then, young people almost always went there to see what was going on. As an 11 year-old, Wendell Brunious fell in love at the pharmacy in Circle Foods — with trumpeter Lee Morgan and other great post-war players:

WB: In the pharmacy right there they had a record rack with cut out records. $1.99. I saw this Lee Morgan and I didn’t know who Lee Morgan was. They had a record there called, “Candy.”I was like, “Well, I have a $1.99.” I was … delivering groceries and packing shelves and all this kind of stuff. I went home and put that record on and listened to Lee Morgan. He played so funky and stuff like that! It just reminded me of my brother John a lot. I was like, “Wow.” Then I heard him play this “All the Way.”

GT: You mean the ballad “All the Way”?

WB: “All the Way.”

GT: That is a gorgeous ballad.

WB: Lee Morgan played that thing! About a year ago I recorded it my way with a lot of Lee’s influence. Thank you Lee Morgan, for recording that. I was a kid I was getting abreast of that sound kind of… I knew the bebop stuff from records my brother had.

GT: Your brother John, Jr.

WB: When I started checking out Lee Morgan, then I found Blue Train.

GT: From John Coltrane of course.

WB: Yeah, and Lee Morgan was playing trumpet on there. Lee Morgan was I think 19 years old.

GT: A baby.

WB: Boy, he played. Man, wow. Then I heard about another Blue Note record of Clifford Brown on that playing, “Get Happy,” [sings]. And I got so I could hum JJ Johnson [sings melody]. It wasn’t, it was kind of post-bobbish. It had a lot of bebop in it, but they were playing standard tunes, but not just playing all kind of crazy stuff, they were really spelling those chords.

GT: This is all from the Circle Foods store?

WB: Yes!

GT: On St. Bernard Avenue.

WB: On St. Bernard Avenue, not even a record store!

GT: From the pharmacy.

WB: Yeah, from the pharmacy in a grocery store.

GT: You know, when you think about it they should have records in the pharmacy. That makes people feel far better than the medicine does sometime.

WB: And no side effects.

A Mere Bag of Shells

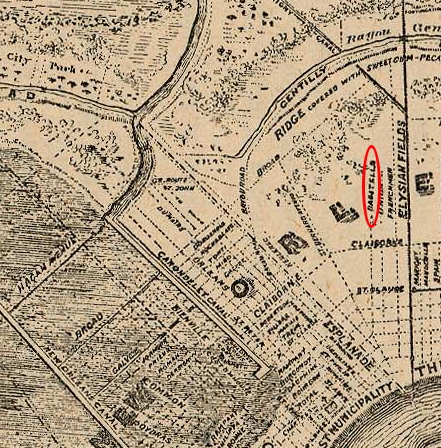

During our interview, Wendell Brunious recalled making up lyrics to “Bagatelle,” a song his father wrote. He says it got that name from a nearby street. “Bagatelle was the name of Annette Street, which was at the corner of our house. An old guy named Mr. Marchand, he told my dad that that used to be named Bagatelle Street a long time ago, before neighborhoods were developed and stuff like that…”

This story piqued our journalistic curiosity and we went looking for Bagatelle Street. A quick on-line search turned up its origin, thanks to Ned Hémard, who writes a weekly history column for the New Orleans Bar Association. He tells us that the game of bagatelle (a distant relative of modern-day pinball) was all the rage in late 18th century France. Once it made its way to New Orleans it became a favorite pastime of Bernard de Marigny, the wealthy landowner whose surname is a New Orleans neighborhood.

According to Hémard, Marigny decided to name a street in honor of the game he enjoyed. You can see it on a city map from 1849:

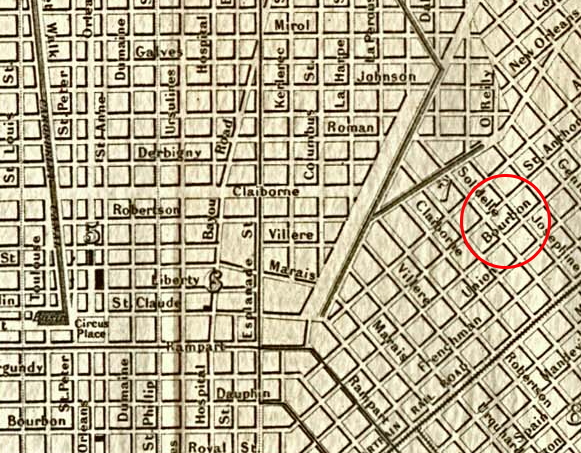

From there, things turn a bit mysterious. A map from 1877 shows Bourbon Street where Bagatelle used to be:

What about Annette Street? It’s on the other side of St. Anthony from Bagatelle/Bourbon. Sorry to say, Mr. Marchand’s memory may have failed him on that score.

These days after Bourbon Street crosses Esplanade it turns into Pauger Street, named for French engineer Adrien de Pauger. Although just when Bagatelle became Bourbon became Pauger is unclear.

Anyone with more information on Bagatelle Street, please drop us a line or comment on Facebook.

Playlist

Here is a playlist of the songs featured this hour. Please support your local musicians and record stores.