Jason Marsalis

Craftsman

As a child, Jason Marsalis watched old television shows as much for the music as for anything the characters were doing onscreen.

“I became a big fan of reruns of the tv show, The Monkees,” he tells Gwen, “My father thought it was just hilarious that I was into this. But when I look back on it, that was music from the 1960s.”

For an 11 year-old, there’s not much difference between the 1960s and the 1920s. And that’s why Marsalis became equally enchanted by Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings. The Hot Seven were particular favorites, because that group featured Warren “Baby” Dodds on drums. The meticulous Dodds remains a hero.

“The musicians back then were more like craftsmen,” Marsalis says, “Music wasn’t a hustle for money. It wasn’t a ticket to stardom. It was a craft.”

Marsalis has adopted the same approach. Despite universally positive reviews for his five albums as a band leader, a platinum surname in jazz and a busy touring schedule, he frequently admonishes himself to practice more and do better by his instruments.

“I think if you are always a student of the music there is always something you can learn,” Marsalis says,”There is always something that you can push for. That’s something the real masters understood.”

Jason Marsalis has stayed plenty busy since we last spoke. He’s moved to France, returned home to New Orleans, continued to tour, and has appeared on numerous new albums and EPs.

As a band leader, he released Heirs to the Crescent City in 2016, Do For You? in 2017, and Melody Reimagined, Book 1 in 2018. He’s also backed up Marcus Roberts in several projects, ranging from his trio to large ensembles, and has appeared on two albums by Norbert Susemihl in 2018 alone.

For a listing of upcoming shows, check out Marsalis’ tour schedule here.

More on Jason Marsalis: Facebook | iTunes | Discography |This program’s Playlist

Find out how you can support Music Inside Out.

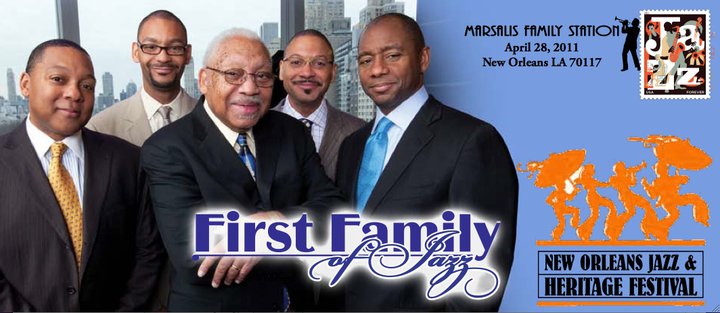

The First Family

Ellis Marsalis and his four musical sons have often been described as “The First Family of Jazz. ” In fact, that’s what they’re called on the U.S. Postal Service’s 2011 collectible Jazz Fest mailing envelope. But Jason Marsalis calls that title, “inaccurate.”

“It’s complimentary,” Jason says, “But we’re from New Orleans. We know better.”

New Orleans is full of musical families, dating back to the beginning of jazz. The Barbarins, the Cottrells, the Lasties, the Gabriels, the Batistes and the Jordans are just a few of many.

Marsalis says his family is anomalous because neither his father, Ellis (who died in 2020, after this program aired), nor his brothers Branford, Wynton or Delfeayo had an early interest in New Orleans traditional jazz. Instead of listening to Louis Armstrong and the Hot Five or Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers, they were all ears for more modern heroes like trumpet players Clifford Brown and Miles Davis or r&b stars Marvin Gaye and Earth Wind and Fire.

Jason says the family’s traditional jazz roots are on his mother’s side. Dolores Marsalis (neé Ferdinand) is a distant cousin of the clarinetist Alphonse Picou. His solo on the early 20th century classic, “High Society,” is still turning heads. Other distant maternal cousins include bassist Marlin Young, who reportedly played with Duke Ellington, and New Orleans trombonist Wendell Eugene.

Playing the Floor

During the early days of jazz recording, drummers played everything but the drums. Wood blocks, cymbals and sometimes the floor would suffice.

“You had to make do with what you had because technology then couldn’t handle drums,” Marsalis says, “Drums were just too loud. They weren’t even loud drums, but the mics just couldn’t handle (the volume).”

Now, drummers like Marsalis play the floor, or the street, as a throwback to that earlier time.

At Marigny Recording Studio, Marsalis played neither floor nor wood blocks. But he did show us a thing or two on the vibraphone. Notice the frown at the end. He’s never quite satisfied. But he owned the floor.

Hall of Fame

Jason Marsalis has a long list of musicians he admires, from traditional jazz players to bebop stars to a French vibraphonist he’s hoping one day to meet.

Here’s a tiny sample of Jason Marsalis’s favorites:

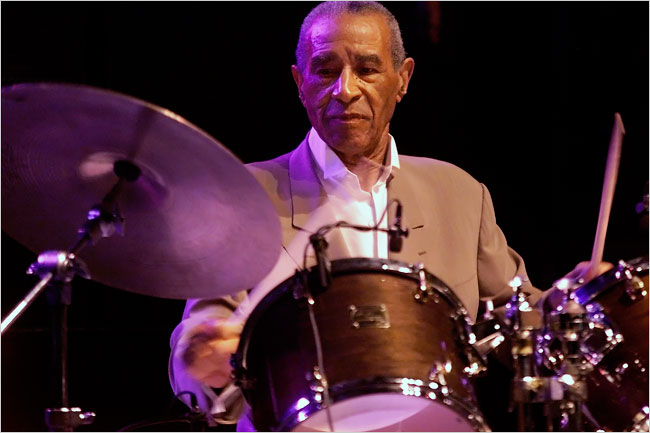

Warren “Baby” Dodds

(1898-1959)

Innovative drummer and reportedly the first to experiment with a variety of patterns in a single recording. Played with Louis Armstrong’s Hot Seven, Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. Later played with clarinetist Jimmy Noone, trumpeter Bunk Johnson and band leader Mezz Mezzrow. Dodds also performed regularly with his younger brother, the clarinetist Johnny Dodds, who was a member of Armstrong’s Hot Five.

Check out the CD, “Baby Dodds Trio Jazz a la Creole”

“Papa” Jo Jones

(1911-1985)

Called a “magician” on drums, Jones played 15 years with the Count Basie Orchestra. He also led his own ensembles and is featured in the celebrated 1957 CBS program, This is Jazz, alongside Billie Holiday, Ben Webster, Lester Young and Danny Barker, among others.

“He used to play really fast,” Marsalis says, “Just unbelievable. Just ridiculous. There is a (recording) with Lester Young and Teddy Riley (Pres & Teddy) where you can hear his cymbal, you can hear his solos, his drum sound, his brush sound. He was another craftsman.”

Jo Jones also looked happier on the bandstand than almost any other musician.

“There was so much joy in the music and you had musicians who loved playing,” Marsalis says, “They wanted to sort of give that to the audience.”

Check out Jones’ work on the Lester Young/Teddy Riley selection, “Louise.”

Max Roach

(1924-2007)

Early bebop drummer, percussionist and composer. Roach emphasized lyricism in drumming. Deeply involved in the civil rights movement. Once called a “political drummer” by The New Yorker magazine.

“Max turned the drum solo into an art form,” Marsalis says, “He played a lot of lyrical ideas. But there was one solo on a record that really, really changed my whole view of drum solos. The album is called, Percussion Bitter Sweet, and the first tune is called, Garvey’s Ghost, named after Marcus Garvey.”

“You have these percussionists that were playing (during the solo). You had a troubadour. Then there was a cowbell. So they are playing this thing and Max leaves all this space in his solo (for them). And it made me think about my own solos. So I decided to leave some solos with space.”

Norbert Lucarain

(b. 1969 Fontenay aux Roses, France)

Vibraphonist, drummer, composer and human beatboxer, double-headed mallet inventor. Lucarain has been described by his collaborators as a “poet and engineer.”

“This dude can play,” Marsalis says, “He has incredible technique. I realized (his) music was not based in the blues, but it was based in in European folk music. I will tell you, there is one tune that I’ve written that I would like to hear him play called, ‘Ballet Class.’ He would tear that apart. He would play it better than I would.”

Marsalis recommends Norbert Lucarain’s composition titled, Noctambule from the 2003 album, Nocatambule.

Check out “Ballet Class” on the CD titled In a World of Mallets by the Jason Marsalis Vibraphone Quartet.

Shannon Powell

(b. 1962 — New Orleans, La.)

Drummer, percussionist, band leader and “The King of Treme”

One of the world’s most dynamic ambassadors of traditional jazz. Formerly played with the Harry Connick Trio. Recorded with John Scofield, Maria Muldaur, Danny and Blue Lu Barker and with his own band.

“I’ve learned things from him while we’re playing together on the band stand,” Marsalis says, “A great and very powerful drummer. He’s a gentleman. I’ve learned a lot from, not only playing drums but I’ve had a chance to play vibes with him as well and I’ve learned a lot even there.”