Tom Sancton

Family Man

It’s About People Coming Together Over Barriers

In the early 1960s, New Orleans was like any other destination on the Gulf Coast — hot, steamy and segregated, sometimes violently so. But the irrepressibly vibrant music culture of the city inspired civil disobedience among musicians and fans. In 1962, veteran African-American musicians at Preservation Hall became mentors to little Tommy Sancton — a young white clarinet student and devotee of traditional jazz. For two years, Sancton and his parents exchanged hospitalities with the men that were expressly forbidden by law. But in the summer of 1964, the Civil Rights Act brought the nation to its senses and laid a legal foundation for friendships across the color line to grow.

As a teenager, Tommy Sancton went on to play regularly with some of the great African-American artists of the day — clarinetists George Lewis and Willie Humphrey at Preservation Hall, and along parade routes with Harold “Duke” Dejan’s Olympia Brass Band. For Sancton, the experience was an education far beyond what he was learning in school.

“For a 13 year-old to be hanging around with, worshipping, learning from and laughing with and eating with and playing parades with guys in their 60s and 70s and sometimes 80s or 90s — this was an exceptional thing,” Sancton tells Gwen. “I think it enriched me as a human being.”

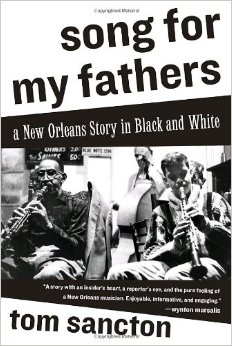

Song for My Fathers

Sancton’s 2006 memoir, Song for My Fathers: A New Orleans Story in Black and White, pays tribute to his biological and musical fathers.

“I always say that the book … deals with music, but it’s not about music, per se,” Sancton says. “(I) always say it’s about people coming together over barriers. That’s really what it’s about. The barriers are … racial barriers, economic barriers, class and generational barriers. ”

Song for My Fathers is available as an e-book, or you can still find the old-fashioned print version online or at your favorite local bookstore.

More on Tom Sancton

Twitter | Apple Music | Website | Wikipedia

Playlist

Each week we provide a playlist of the music heard on the show. Our hope it that you will download it to your phone (or print it) and take it with you to your local record store. Help support the musicians who make the music we love — and the local retailers who sell it.

Civil Disobedience Never Sounded So Good

African-American street vendor Dora Bliggen (1892-1977) knew she was breaking segregation laws when she recorded her “Blackberries!” song at Tom Sancton’s childhood home in uptown New Orleans. It was circa 1955. Sancton’s parents and their musicologist friend, Charles Frederick Ramsey, Jr. , were also breaking the law. They’d bought Bliggen’s entire cache of fruit and had still invited her into the home. At the time, black and white people weren’t supposed to socialize in New Orleans under the same roof. But Ramsey was collecting regional folk songs and the Sanctons knew Bliggen had a winner. She recorded “Blackberries!” and three gospel selections in the Sanctons’ living room. Bliggen’s songs are available on a CD titled, “Classic Sounds of New Orleans from Smithsonian Folkways.” “I still listen to the recordings today,” Sancton says.

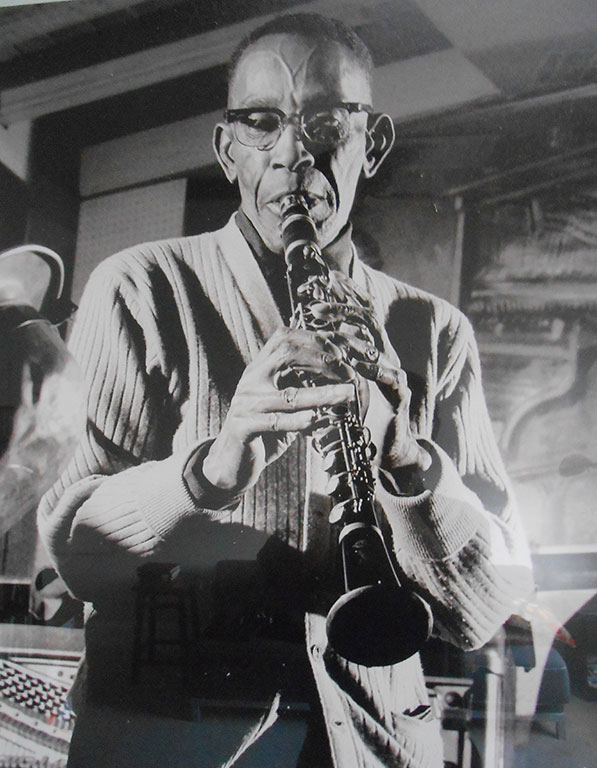

Meet George Lewis

New Orleans has produced an embarrassment of brilliant clarinet players, including Sidney Bechet, Alphonse Picou, Willie Humphrey and Louis Cotrell, among others. But George Lewis (1900-1968) holds a special place in the hearts of many traditional jazz musicians. Lewis, who toured and recorded with the pioneering Bunk Johnson in the early 1940s, was later a star at Preservation Hall. Known for an ethereal tone, sometimes called “angelic,” Lewis is perhaps best known for his song, “Burgundy Street Blues.” That song kindled a newly found passion in the young Tommy Sancton. It also made an indelible impression on other contemporary clarinet players such as Sammy Rimmington and Dr. Michael White.

Lewis became the young Sancton’s inspiration and particular friend. He was also a friend to the Sancton family. Dogged by ill health through much of the 1960s, he died on the last day of 1968.

Lewis was not a formally-trained musician, nor did he read music. But his contribution to the international appeal of traditional jazz was deep enough to draw nearly every jazz musician in New Orleans to his funeral, as well as media and fans from around the world. Tommy Sancton came home from his studies at Harvard University to play in Lewis’ funeral parade.

Meet Creole George Guesnon

One of the most forceful characters in Tommy Sancton’s young life was banjo player, Creole George Guesnon. A close friend of Olympia Brass Band leader, Harold “Duke” Dejan, Guesnon (1907-1968) had attended elementary school with the reknowned banjoist Danny Barker.

Many of the young Sancton’s mentors had urged him to spend time with African-American musicians; to apprentice with them and absorb lessons that would improve his clarinet play. But Guesnon (pronounced: GAY no) was intent on teaching Sancton specifically about African-Americans of Creole descent in New Orleans, a group that he called “a race within a race.”

“He taught me a lot about all this history and about attitudes,” Sancton says. “ … He’d put a stocking on his head. He had wavy hair and he had this pomade. He said a lot of Creole musicians wouldn’t talk to anybody that didn’t have silky hair.”

What separated Creole and non-Creole African-Americans socially in New Orleans went far beyond differences in physical features, Guesnon told Sancton. The story is rooted in colonial Louisiana and the Code Noir, which recognized Creole free people of color. And distinctions between Creole and non-Creole black people were still being made long after the Americans came. In the 1960s, Sancton says that even he noticed “a kind of discrimination within the colored community.”

“But when they were all together on the bandstand they were actually just jazz musicians, New Orleans jazz musicians playing together. So the music really was a kind of cultural melting pot.”

Guesnon was a serious writer and composer, but could never achieve commercial success. Before he died, Guesnon burned much of his original material.

“The tragedy of George Guesnon is he was this man with all this talent and ability and ambition, locked in the body of a man of color in the South, in New Orleans, in the time he grew up,” Sancton says. “All his doors were just locked.”

What’s That Under the Bed?

For about a dozen years, Tommy Sancton put away his clarinet to earn a doctorate in history at Oxford University and later to pursue a life in journalism.

“I figured I couldn’t play jazz and do anything else, really,” Sancton says. “I was that passionate about it . So (I thought) if I’m going to have a normal career where I get my degree, get an adult job, start paying Social Security, stuff like that, I’ve got to renounce music.”

Sancton spent the bulk of his journalism career as a reporter and editor for TIME Magazine, including nearly a decade as Paris bureau chief. He also co-wrote a best selling book about the investigation into the death of Princess Diana.

But Sancton eventually rescued his clarinet from obscurity. He’s recorded and appeared on more than a dozen albums and nowadays, he plays more gigs than ever.

“… I don’t think I ever had the ambition to be great with a capital G like … Duke Ellington or Benny Goodman or Louis Armstrong,” Sancton says. “I don’t need people to say, ‘Okay, who is the greatest clarinet player that ever lived? Tom Sancton.’ I can live without that. I just wanted to play that music. ”

Tom Sancton, Sr.

“He thought George Lewis was like Agamemnon”

Perhaps no figure wielded more influence over young Tommy Sancton than his father, Tom Sancton, Sr. A journalist, novelist and traditional jazz fan, Sancton introduced his son to Preservation Hall and grew close to the musicians who played there.

Sancton (1915 – 2012) worked at the old States-Item newspaper in New Orleans and later became managing editor of The New Republic Magazine. During his tenure at the magazine (1942-1945) and later at LIFE, Sancton wrote countless articles calling for an end to segregation and urging like-minded but inert liberals to become active in the cause. Mississippi lawmaker John Rankin, a segregationist, once denounced Sancton’s articles on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives. But Sancton reportedly considered the criticism a compliment.

Sancton returned to New Orleans in the late 1940s to write novels. He later contributed to New Yorker writer A.J. Liebling’s stories about Louisiana Governor Earl Long and the state’s 1960 gubernatorial race. Their reportage resulted in the book, The Earl of Louisiana, still considered by many to be the most insightful examination of race and Louisiana politics.

“He was very well read,” Tom Sancton, Jr. says of his father. “He read all kinds of things and was particularly interested in the Greek classics. Homer he knew by heart. He saw the musicians (at Preservation Hall) as heroic figures, the universal archetypes of some universal characters. He mentioned that to Allan Jaffe. Allan Jaffe at that time was a young man running Preservation Hall. Allan years later repeated that to me and said how much it impressed him and gave him a sense of the universal importance of what they were doing. “

The Bettencourt Affair

In August, 2017, Tom Sancton’s most recent book, The Bettencourt Affair, was released by Dutton publishing house. The biography follows the life of the world’s richest woman and L’Oréal heiress, Liliane Bettencourt, and her relationship with photographer François-Marie Banier, which culminated in a 2010 scandal that reached into the highest levels of the French government. But we don’t want to give too much away. You can hear Sancton talk about the book with NPR’s Scott Simon here, or get a copy from Penguin Random House or your local bookstore.