Walter Wolfman Washington

Liner notes by Gwen Thompkins, host of Music Inside Out

When Walter “Wolfman” Washington (1943-2022) started recording this album, he did not yet know it would be his last. The words and music now feel somewhat bluer than he originally intended, the sound inevitably more profound. And yet, there’s a relaxed quality here, a quarter-to-three-like mood evoking cocktails and cigarettes and nighttime musings that spill unresolved into day. The subject is romance, a Washington favorite, and the songs move like a numberless time piece through phases of a lover’s tale: twilight, dawn, the golden hour, the blue hour, dusk, midnight, first light.

Feel So At Home is a continuation of the work that Washington and producer Ben Ellman (Galactic) began years ago, when they decided to drape his music in quiet and bring the listener closer to the man he was inside. Nearly every mature artist wants to try. That initial departure from the high volume of Washington’s live sets with his band The Roadmasters — isolating him from the electric company of his trusted blues, r&b, soul and funk-playing sidemen — had resulted in the 2018 album My Future Is My Past, an artistic summit.

A History On The Road

Washington had come a long way since his early performing days in the late 1950s, when he’d backed his cousin, the r&b artist Ernie K-Doe (“Mother-in-Law”) and then accompanied Lee Dorsey (“Ya-Ya”) at the Apollo Theater in Harlem and later on tour. He also worked plenty as a sideman and bandleader for the soul queen Irma Thomas, for his mentors Johnny Adams and the saxophone player David Lastie, and for other New Orleans musical greats.

Washington was the house band leader at the regionally famous Dew Drop Inn for a spell, before becoming a regular performer at Terrol’s Lounge, Dorothy’s Medallion, Charles’ Medallion, the Maple Leaf Bar, Tipitina’s, Tyler’s Beer Garden, Benny’s, Snug Harbor, Muddy Waters, d.b.a., and dozens of other venues in New Orleans and beyond city limits.

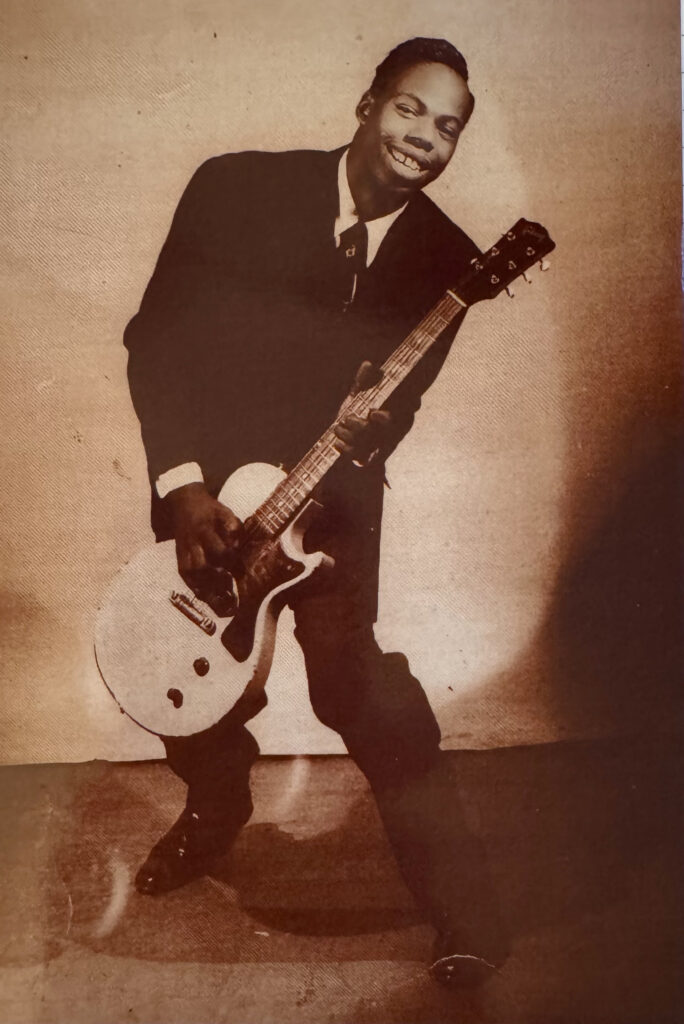

His consistency, song-writing and flair paid off, earning him a reputation in middle age as a reliable crowd-pleaser. Of medium height and as thin as a minute, Washington became known for howling, picking the electric guitar with his incisors, riffing with remarkable deftness and panache, projecting his baritone seamlessly from shout to growl to falsetto, and riling up audiences to join him in song. And yet, his deepest blues were unusually fine. There was a tenderness in him that was always and undeniably present.

On My Future is My Past, Washington showed himself to be a credible jazz balladeer. Within the hush of acoustic understatement, he swung gems from the American Songbook. He sang locally-forged songs evoking the terroir of a Louisiana night. He covered love’s regrets with Irma Thomas in a duet by songwriters David Egan and Buddy Flett. And yet, the spare musical setting mostly put Washington in conversation with himself. On the chorus of his joyfully intimate “What a Diff’rence a Day Makes,” he seemed tickled by the man it had taken him nearly eight decades to become. And the difference is you … indeed. Washington expected this latest project with Ellman to position him and his guitar more comfortably in the blues, but this time with strings and other aesthetic choices that would continue to frame him anew.

The Musicians

Recording began in the immediate afterglow of My Future Is My Past at a variety of studios around New Orleans — the old Parlor, PJ Morton’s Gumbo Studios (formerly the Music Shed), and at Ellman’s own home studio for the finishing vocals and post-production. Bassist James Singleton (Astral Project) and drummer Stanton Moore (Galactic, the Stanton Moore Trio) reprised their roles from My Future is My Past, as did Roadmasters veteran Steve DeTroy (The Catahoulas) on piano. Feels So At Home also features a woodwind and horn section provided by Nick Ellman (Naughty Professor, Maroon 5) a cousin of the producer, and a one-man string section courtesy of the multi-instrumentalist Rick G. Nelson (Afghan Whigs) who plays violin, viola and cello. Guitarist John Michael Rouchell joins on electric sitar.

For the longest time, no one seemed to be in a rush to finish, least of all Washington, who was enjoying a long victory lap around the city. In 2018, he’d won the New Orleans Big Easy Awards for lifetime achievement, best blues album, and album of the year. (Ellman also won for producer of the year.) And in 2019, he had reigned as king of Krewe du Vieux, one of the city’s most anticipated carnival parades — a distinction that means more to a New Orleanian than almost any other. Then, the coronavirus pandemic silenced the city for nearly two years before work on the project resumed. And yet, the songs flow with notable cohesion. Washington’s last album is a color wheel, saturated with various intensities of blue.

The Songs

The opening salutation “I Feel So At Home Here,” begins with an overture — a rising, anticipatory breath of woodwinds, horns, drum cymbals, sitar, bass, and piano that pauses dramatically for Washington to make his presence known. His electric guitar chords sound half blues and half country then, reminiscent of Brook Benton’s “Rainy Night in Georgia” and other broadly popular Southern ballads of the 1970s. The song, co-written by jazz singer Michelle Wiley and Ed Townsend, originally depicted a woman relaxing in the lair of her soon-to-be lover. Nearly 50 years after its 1977 release, Washington turns the tables and he becomes the visitor who’s sighing relief.

Ironically, the original arranger on “I Feel So At Home Here” was René Hall, yet another Louisianan. Hall was a jazz contemporary of the New Orleans guitar and banjo player Danny Barker, and a respected West Coast music maker from the 1950s to the late 1980s. He arranged a number of releases for Sam Cooke, including the civil rights anthem “A Change is Gonna Come,” which also begins with a symphonic overture and makes ample use of strings. On Washington’s version of “I Feel So At Home Here,” the delicate layer of strings not only gives the record a timeless feel, but a sense of optimism for what lies ahead.

“Without You” returns Washington more directly to the blues and deeper hues on the blue color wheel. The song, which he wrote, originally appeared on his 1986 Wolf Tracks release, conjuring the mid-twentieth century heyday of New Orleans rhythm and blues. It’s a lover’s lament, but danceable, and the original arrangement featured horn-filled breaks working up to a startling Washington falsetto. In this latest version, he appears to have the emotional distance to showcase the beauty of the lyrics. He delivers slower, with more sophistication and no falsetto, supported by a superbly understated rhythm section and a whisper of elevating strings.

Producer Ben Ellman says Feel So at Home is a song cycle intended to be heard in a single go, and the 1950s slow drag “Along About Midnight” introduces an electric blue tone to the listening experience — along about lapis lazuli, maybe, on the blue color wheel. The arrangement reunites Washington with his guitar, presumably the one he called “Big B,” and he takes every possible advantage.

“Along About Midnight,” which was written by his Mississippi-born uncle Eddie Jones, a.k.a Guitar Slim, also reminds listeners of how deeply rooted Washington’s family is in 20th century American popular music — his future was quite literally his past.

The protagonist of the song gives testimony, sharing his remorse for the loss of romantic, maternal, and agape love. Then, he lets his erupting guitar confess the rest. Later on the album, Washington dips yet again from Guitar Slim’s discography with his own version of “Sufferin’ Mind,” a dance song that conjures those splendid rhythms of 1950s New Orleans r&b — high volume bass, drums, inferred piano triplets, and all. Rarely has contrition sounded this fun.

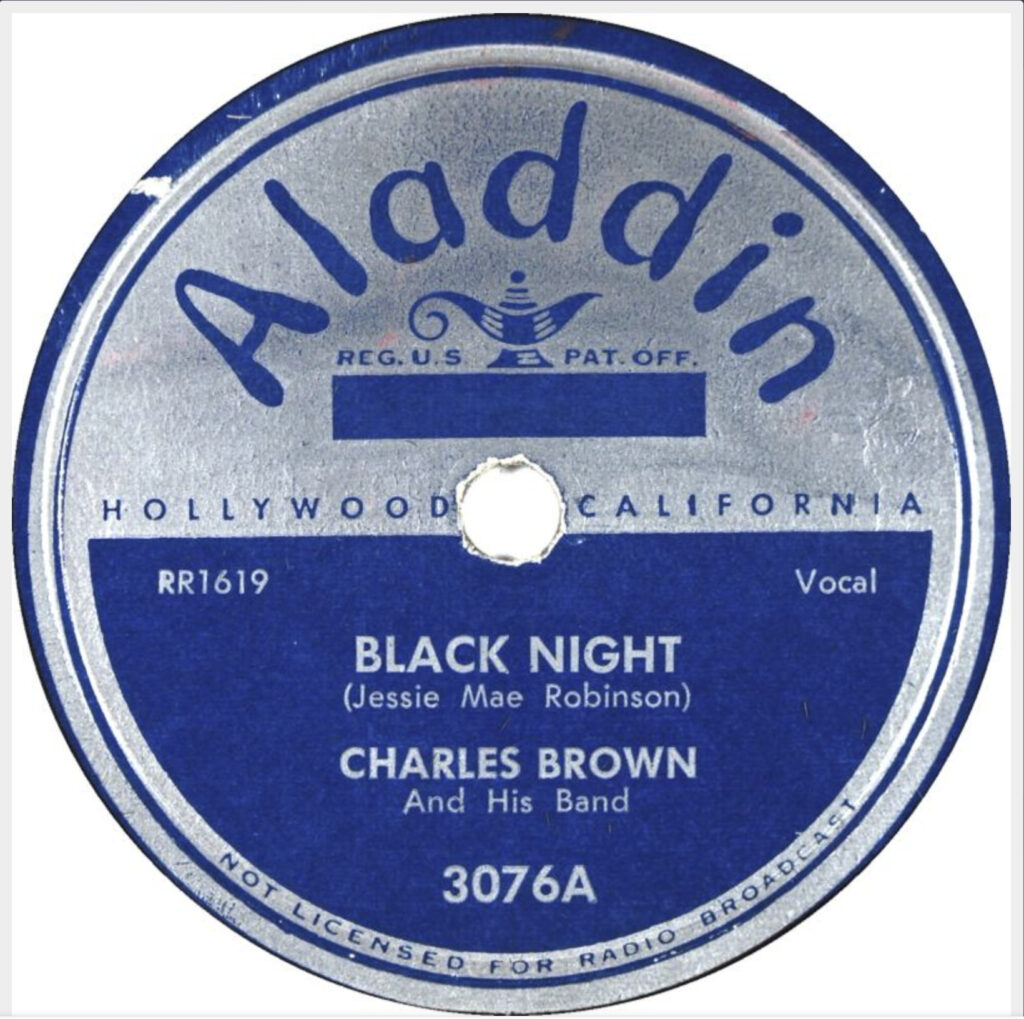

Charles Brown made “Black Night” popular as far back as 1951, but thanks to the lingering genius of piano wizards James Booker and Mac Rebennack, a.k.a. Dr. John, the song remains a staple of the New Orleans repertoire. Written by Jessie Mae Robinson, Washington’s version of “Black Night” keeps the guitar in the foreground, sometimes with David Torkanowsky’s piano. But it’s Washington’s vocal that communicates the song’s meaning. He delivers each word as if he happened to think of it while standing in front of the mic. That immediacy makes the song sound as fresh as a hot donut. Glazed.

My mother has the troubles, my father has them, too

My brother’s at Angola and I don’t know what to do

Black night is falling and how I hate to be alone

I keep crying for my baby

Now another day is gone

It’s gone, It’s gone

For years, Washington accompanied the multi-octave New Orleans r&b singer Johnny Adams, and the song “It’s Raining in My Life” brings that relationship to mind. Adams could be plaintive in his handling of the blues but rarely sounded as hurt as Washington could. On this version of the song — which Washington originally wrote as the title track of his 1981 album Rainin’ In My Life — Washington seems to be channeling Adams. He holds back on emotion, letting the narrative speak for itself. “It’s Raining in My Life” is a slow-walking blues, with a slapping drum beat that falls heavily like raindrops on a windowsill. It’s no mystery what the song is about. She’s left — this time maybe for good. And the guitar talks back, mirroring the pain.

An insistent rhythm courses through “I’ve Been Wrong So Long” and each pulse feels like rising desire. The song, written by Ray Agee and Don Robey, a.k.a. Deadric Malone, first appeared on Bobby “Blue” Bland’s 1961 critical and commercial juggernaut Two Steps from the Blues. In Washington’s song cycle, his version of “I’ve Been Wrong So Long” signals a shot at redemption. Maybe he can win her back.

Now darling, let me make sweet love to you

Come on and tell me what you want me to do

Now I know, oh yes I know

That I’ve been wrong for so long

Washington sings as if the guitar taught him how — finding blue notes that only a lifetime on the band stand could teach. His growls and pleadings and those big major chords make the song sound not only sincere, but visceral … and sexy.

And yet, “Lovely Day” is the highlight of Feel So At Home, perhaps because it allowed Ellman to see Washington as if for the very first time. “Lovely Day” is about just that — happy hours spent with someone, a spouse, a friend, an old acquaintance, perhaps, or a new infatuation. The song, which Washington wrote, appears as a valentine on his Rainin’ In My Life album. But on Feel So At Home the musical arrangement is more spacious and his long trailing notes invite listeners to revisit their own happy memories and make them last. In March of 2022, just after his diagnosis of cancer of the tonsils and just before his voice gave out for good, Washington was having trouble singing “Lovely Day” in Ellman’s vocal booth.

Capturing the Vocal

“I put him on the couch in the control room where I am,” Ellman said, “with (his wife) Michelle and me in the room … without headphones, the speakers were on, and he is just sitting … lights off, listening, singing into a mic. And that was the best vocal we ever got. And it was the easiest. Like one or two takes … And then when we cracked the code, we were like, ‘Oh, I get it, you need to be on the couch singing without headphones, with a joint in your hand. This is how the magic is made. I get it now!’ If we were going to make another record, I would have him do every single song that way.”

That there will be no other records makes the performance resonate even more. It counts as the golden hour of the album — the most brilliantly colored light before sunset on a lover’s day. But the beauty of this eight-song cycle is that it can reset, returning Washington momentarily to first light.

Gwen Thompkins

August, 2023

Gwen Thompkins is a journalist based in New Orleans and the executive producer and host of Music Inside Out.

Feel So At Home is available through the Tipitina’s Record Club.