Ellis Marsalis Jr.

1934–2020Jazz Patriarch

By the time a jazz musician reaches the age of 85 and has appeared on more than two dozen albums, when the National Endowment for the Arts has named him a “master” and the U.S. Postal Service has put his face on a stamp, if an educational center for children in New Orleans bears his name and a generation of internationally-known musicians counts him as a vital influence, chances are that most people know he’s Ellis Marsalis Jr.

A 1999 biography, a sister and a brood of sons can attest to the details of Marsalis’ life story. But there’s nothing like a first-person account from an extraordinary musician talking about the arc of his creative struggles and accomplishments. Few worked harder or longer than he did to carry the message of modern jazz as both a musician and educator. When we spoke with him in 2017, he still was working professionally as the leader of the Ellis Marsalis Quintet and writing a curriculum for teaching jazz in schools.

“There are things I have to do, need to do, have started and need to complete,” Marsalis told Gwen. “So that thinking about my life is kind of an egotistical luxury.”

He died in April, 2020 of pneumonia, brought on by the coronavirus.

Early Life

Marsalis’ never-ending to-do list began when he was a ‘tween in the mid-1940s. That’s when he fell in love with jazz on the radio and committed to spending his life in music. His parents had moved the family to a then-rural area, just outside the New Orleans city limits. There, in the lap of nature, young Ellis listened to WJBW-AM and other stations, and said the music he heard “spoke” to him.

Marsalis’ father, Ellis Sr., a pioneering, Mississippi-born, black entrepreneur in an era of intense segregation, was managing a filling station in the city. He had worked other jobs as well to earn enough money to buy a tract of fertile land in Jefferson Parish. He settled his wife and two children there with plans to become a gentleman farmer.

Ellis Sr. hoped to raise chickens but, his son recalled, “the chickens didn’t lay no eggs.” There were fruit trees, though – plantain, satsuma and mulberry – and a couple of cows.

EM: “There were times when it was my responsibly to kill the chickens, heat up the water and take all the feathers and all of that off so it could be cooked. But that lasted about two years. I never did learn how to milk that cow.”

Marsalis Mansion

Eventually, Ellis Sr. converted the barn into a public meeting space with a few rooms for sleeping. The building accommodated members of the National Urban League and other African-American travelers who weren’t welcome to stay in the city. Word of mouth spread, and by 1950 — the family had a motel boasting 35 rooms and a pool. The Marsalis Mansion was in business.

EM: Well there were lots of people who stayed in there. Martin Luther King stayed once. Ray Charles and the band used to stay there. BB King. Dinah Washington did. She stayed there because … there was no other place that was around except people in their homes that would house musicians coming through town, because there was no place for them to stay. I think in the peak years he had nine people working.

From Swing to Bop

And yet, despite Marsalis Mansion’s clientele, R&B did not speak to young Ellis. With his ears and heart softening to jazz, he took formal lessons in piano and non-vernacular clarinet, partly inspired by hearing the band leader and clarinetist Artie Shaw on the radio. Ellis Jr. also told Gwen about listening to Woody Herman and Bing Crosby and anyone else appearing on the Hit Parade. But recordings by Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra, Charlie Parker and Miles Davis set him on the path that he would pursue for the next 60 years. Modern jazz ensembles playing bebop presented the creative challenging he’d been looking for. Later, Ellis Jr. switched from clarinet to tenor saxophone and for a while played both professionally.

EM: “…fortunately I had a piano teacher, her name was Jane Coston Maloney and she taught me fundamentals of the instrument, but I was not with her long enough to develop that beyond that point. But I had a good foundation. I would play a job here, a job there, sometimes on piano. Sometimes saxophone. It was a real disorienting, disorganized, helter-skelter kind of life style.”

American Jazz Quintet

Picture these fellows as children. Ellis, Jr. met clarinetist Alvin Batiste in grammar school. He and drummer Ed Blackwell also met as children and saxophonist/producer Harold Battiste, Jr. became Ellis’ mentor at Dillard University in New Orleans. None of the universities they attended would support a jazz curriculum, and some were actively anti-jazz. But as young men, these musicians banded together with Richard Payne and/or Chuck Badie (not pictured) on bass and formed The American Jazz Quintet.

In 1956, the group made one of the first New Orleans modern jazz recordings at Cosimo Matassa’s legendary studio. Ellis Jr. was just 22 years old. The American Jazz Quintet didn’t get many gigs, but the bond they formed lasted a lifetime.

Art v. Commerce

As it turns out, the biggest pitfall of playing modern jazz back when Marsalis began in the late 1940s remains the biggest problem still. “There was no way to visually see that you could make any money at it,” he told Gwen.

EM: ”A lot of times people will ask questions like, ‘Man, what can be done to make jazz more popular?’ Well, if it becomes more popular, it is more likely not to be jazz! Jazz primarily started, like a lot of other music, as folk music. But the musicians who decided that they were going to be creative inside of that – like Duke Ellington had a dance band. Count Basie had a dance band. Stan Kenton had a dance band. They all had dance bands. Eventually, as things changed, people started dancing to different kinds of music. Technology came into play. All variations of a lot of things. Right now, what we have known and are still knowing to be jazz, is being presented to some younger people who have decisions to make about that.”

To L.A. and Back to LA

After graduating from Dillard with a degree in music education, Marsalis enlisted in the Marines for two years, where he played in military jazz quartet featured on a Sunday afternoon TV show called “Dress Blues.” It was there, he said, that he learned to handle a variety of different music styles. But when Marsalis got out, in 1958, he had a decision to make.

EM: “My plan was that I – cause I had a car – my plan was I’d take my mustering outfit with me and leave and I’d throw my stuff in the trunk of the car and drive to New York from L.A. but I didn’t do that. I was in a good position to have done it, and knowing even later what I knew about New York, it would have been a perfect time to do that.”

Instead he pointed the car back to New Orleans. “I think that I was being spiritually guided above and beyond the decisions that I was making, which turned out to be the best thing for me to do.” Dolores Ferdinand would agree. They met at a Dinah Washington concert. The two married in 1959; a marriage that lasted until Dolores’ death in 2017.

Performing and Teaching

For the next four decades, Marsalis worked anywhere and everywhere — as a soloist, a sideman and a band leader. At the Haven, he played a jam session with John Coltrane and McCoy Tyner. Later, he toured for three years with trumpeter Al Hirt. He played the Playboy Club on Bourbon Street and scores of other music venues. He played at churches, brunches and cocktail hours. And he led ensembles featuring some of the city’s best known modern jazz musicians, including James Black (d), Nat Perrilliat (sax) and Herlin Riley (d).

The Hyatt Regency Hotel opened a club with Marsalis in mind to anchor it. There, he played with trumpeter Clark Terry and saxophonist Eddie Lockjaw Davis. For 30 years he had a standing weekly engagement at the Snug Harbor Jazz Club in Marigny, then became a featured guest in his son Jason’s weekly appearances there. Marsalis never stopped playing, often interpreting original compositions written by his bandmates and former brethren in the American Jazz Quintet.

The Audience Is Everywhere

Marsalis told an interviewer in 2001 he learned something from every job. Even playing in the Hyatt atrium, he says, was instructive. “One night, one of the waitresses came by and said, ‘Man, you ain’t played a blues all evening.’ Which I thought was interesting, because I thought they weren’t listening to me.” When he asked if it mattered what he played, he found out all the wait staff fed off the energy in his music. Marsalis says he learned the audience is sometimes more than a person in a chair, listening attentively.

And yet, between the gigs Marsalis lived a full life as a teacher, or “facilitator,” as preferred to say. He earned a master’s degree in music education and was one of the first instructors at the seminal New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts (NOCCA).

EM: “The philosophy at NOCCA was very simple. If you come in and you stay and complete a course, once you complete it, if you decide that you are going to become a professional musician, it was incumbent on us to prepare you for that. If you decide not to, you were prepared anyway.”

To VA and Back to LA

Leaving NOCCA in 1986, Marsalis coordinated jazz studies for three years at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, then returned to home to build a jazz studies program at the University of New Orleans from the ground up. His first hire was former mentor Harold Battiste, Jr., who helped build a curriculum that has endured. Students who attended the program include drummer Brian Blade, trumpeter Nicholas Payton and pianist Jesse McBride, as well as trumpeter Ashlin Parker and saxophonist Derek Douget, who later became members of the Ellis Marsalis Quintet. Marsalis remained at UNO until his retirement in 2001.

The Ellis Marsalis Jr. philosophy of teaching was hands-on.

EM: “…if you can facilitate the student through the material that you use to teach and recommend – ’cause a lot of stuff you recommend are things that you may not have on the spot if we are talking about music. You can tell a student, “Look, what you need to do, you need to go listen to standards.” Now, here is somebody who has been spending all their time trying to play like John Coltrane, so you say, “Hey man, that is okay, but you need to go and check out Sonny Rollins.” Become more like a facilitator.”

Another Piano Teacher

Marsalis was adamant about teaching kids, not “musicians.” He played with them whenever they asked. He says he believed in pragmatism … and sometimes he could be brutally honest.

EM: I was teaching at NOCCA and we would have auditions twice a year. This one young lady came in. She was in elementary school, or high school. … She sits down to the piano and she starts to play with her right hand. I said, “Well what happened to your left hand?” She said, “Well my piano teacher didn’t give me anything to do for the left hand.” I said, “You need to get you another piano teacher.”

Raising a Generation of Stars

Marsalis says he never pushed his sons toward careers in music. Nevertheless, four of them — Branford, Wynton, Delfeayo and Jason Marsalis — are thriving in their chosen profession.

EM: “Somebody asked Delfeayo and Jason, “How do you see your dad?” Delfayo said as a player, and Jason said as a teacher.”

As a tribute to Ellis Marsalis Jr. the musician and educator, his NOCCA pupil Harry Connick Jr. and eldest son Branford built the Ellis Marsalis Center for Music in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward. The Center says its mission is to provide “a safe, positive environment where underserved children and youth develop musically, academically and socially.”

“And the kids who come, they don’t just come from the 9th Ward,” Marsalis told Gwen, “but the point is, I think the kids … who do come there, can see a space which is a first class space, for them.”

Ellis Marsalis Jr. – In Memoriam

Wynton Marsalis posted this tribute to his father:

Branford Marsalis also eulogized his father on his website:

Tribute From Harry

In his website’s bio, Harry Connick Jr. credits two New Orleans piano legends for his early jazz education: “James Booker, who allowed a pre-teen Harry to sit at his elbow in local clubs, and Ellis Marsalis, who provided more structured instruction during Harry’s teenage years.”

About Marsalis, Connick explained “He didn’t care how much talent you had. He just wanted you to be better at what you did.” Harry Connick Jr. recorded a tribute to his friend and mentor in a heartfelt video from his home in Connecticut:

Tribute From Wynton

Each week the Jazz at Lincoln Center Facebook page hosts “Skain’s Domain,” where Wynton Marsalis and guests “talk with enthusiasm and dedication about a gamut of subjects trivial and serious.” In this video they discuss Ellis Marsalis Jr.’s legacy. Participants include Jon Batiste, Terence Blanchard, Peter Martin, Joey Alexandar, Antoine Drye and Clarence Penn.

On YouTube, Wynton Marsalis also led a virtual performance in the New Orleans tradition, called #MemorialForUsAll. It’s described as “a secular community remembrance, welcoming all to celebrate the lives of those who have left us too soon through small gestures of music.” Participants included Wynton and Jason Marsalis, Dr. Michael White, Shannon Powell, Herlin Riley and Wendell Pierce.

Listening to Ellis

As a solo performer, group leader, sideman and guest artist, Ellis Marsalis Jr., has so many recordings – in and out of print – it’s almost impossible to list them all. But there are a few that stand out:

That early American Jazz Quintet session is available, as Gulf Coast Jazz.

The 1963 Ellis Marsalis Quartet Monkey Puzzle recording is available as Classic Ellis Marsalis, with James Black, drums; Marshall Smith, bass and Nat Perrilliat, saxophone.

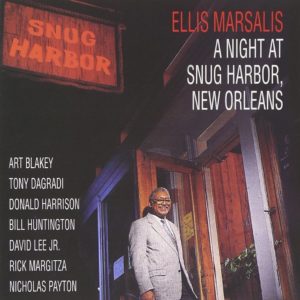

The 1995 album, A Night at Snug Harbor, New Orleans presents the ensemble in a configuration one reviewer called “a jam session for tenor saxophonists Rick Margitza, Tony Dagradi and Donald Harrison … Art Blakey sits in on one tune and trumpeter Nicholas Payton — who was then all of 15 years old — startles everyone.”

Loved Ones

Loved Ones began as a solo album, but Ellis soon invited his eldest son Branford to join him on saxophone.

EM: I started working on all of these pieces and the more I worked on these pieces, I could hear Branford playing this melody. So I just called him and said, “Hey man, look, I’ve to got to do this CD. Come play on this. Just me and you.” And that is what we did. We eventually did. Called it “Loved Ones,” because it was all female type songs.

GT: Yeah, I mean each song was named after… each song bore the name of a woman.

EM: Right. And that wasn’t intentional.

GT: Really?

EM: It actually really wasn’t. It just worked out that way.

Recordings with other Marsalis offspring include Wynton Marsalis’ debut album in 1981, The Last Southern Gentlemen (2014) with Delfeayo on trombone and many with Jason who plays drums and vibraphone.

Here’s a version of the Ellis Marsalis Trio with Jason Marsalis on drums, enjoying themselves at the Louisiana Music Factory in 2014.

Playlist

Each week we provide a playlist of the music heard on the program. It’s our hope you’ll refer to it the next time you visit your favorite music retailer.

Looking Forward

Before his death Ellis Marsalis Jr. said he planned to record compositions by his Monkey Puzzle colleague James Black, as well as some of Horace Silver’s music. The James Black project didn’t materialize, but Jason Marsalis confirms his father’s quintet recorded “half a record’s worth of (Horace Silver) tunes along with lots of other music. It’ll be released some time in the future.”

Saxophonist Derek Douget adds, “He was committed to the idea that a Jazz Quintet was a great vessel for teaching most of the components of Jazz. I won’t speak for him but I think his belief was that a Jazz Quintet was to Jazz as a Symphony Orchestra is to classical music.”

Jazz Skills

As an educator, Ellis Marsalis Jr. believed that jazz is not so much a genre, but a skill.

ET: “Now, the reason is this. The musicians who work professionally today, not so much in symphony orchestras, but like if you turn on an awards show and there is a band in the back, that band is full of musicians who have jazz skills. If it is New York, if it is in L.A., especially if it is in L.A., a lot of them are what they call studio musicians. Musicians who are called upon to go in the studio and record music for a working performer, singer, or what have you. They have jazz skills.”

Jazz skills manifest in surprising ways, Marsalis says:

EM: “… Unfortunately there are too many people who try and describe jazz as being European harmony and African rhythm, which is not true. That is an easy way for them to deal with it. But what it comes down to is, all of the component parts that go into the music at the center and the focal point, is the drum set, because whatever happens to the drum set basically is what the essence of the music is going to sound like.

EM: There was a group, it was a very interesting group, too. A group of singers called the Swingle Singers. What they did, they would read some of J.S. Bach’s music, and they had a bass player and a drummer playing brushes. They would read all the notes just the way Bach wrote it. But, the whole thing swung because of what the drummer and the bass player was doing.

The Silverbook

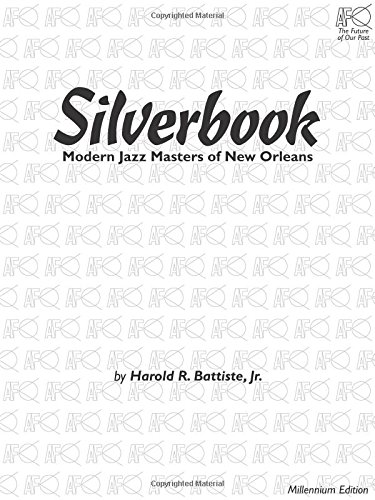

Ellis Marsalis Jr. never considered himself to be a gifted composer, but he left behind a trove of jazz originals, many of which are collected in a volume called The Silverbook.

A kind of vade mecum for aspiring jazz musicians, The Silverbook is, in part, what some players might call a “fake book” – a collection of songs with the melody, lyrics and chord changes written over the appropriate beats. But it’s much more. Marsalis told us that he unwittingly inspired its creation.

EM: Harold Batiste, myself, Alvin (Batiste), (Ed) Blackwell, I think Richard Payne, we were invited up to Atlanta, Georgia to play in what was called an Edward Blackwell Festival.

GT: In the mid 1980’s.

EM: Yeah. Or late 1980’s, really, because I was at Virginia Commonwealth and it was, I think it was close to my last year. Alvin wrote up some songs that we could play. … But as we were getting ready to rehearse … I remarked to Harold, I said, “Man, everything that I know about music is in these songs right here. Not some classroom or none of that.” So, Harold, unbeknownst to me, Harold thought about that and then he went and he created what is now called a Silverbook. The Silverbook is the songs that we played for the better part of 40 years, is in that book. The ones that I played I still remember.

Not Just Lead Sheets

Nine Marsalis songs — “After,” “Basic Urge,” “Cry Again,” “Five for Trane,” “Life’s a Drag,” “Swinging in the Haven,” “Toni,” “12’s It” and “When We First Met” — are among the 61 compositions included in The Silverbook.

In addition to lead sheets, The Silverbook has “commentaries on the rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic information” in each composition, according to Battiste’s AFO Foundation. Along with “observations regarding style, genre, and historic perspective,” The Silverbook is a valuable resource for both students and working musicians. It’s truly a memorial to the “Modern Jazz Masters of New Orleans.”

For All We Know

Our colleagues at WBGO, the Newark-based jazz radio station, have an exclusive behind-the-scenes peek at the last studio album by Ellis Marsalis Jr.

In February, 2020, just weeks before his death, Marsalis and son Jason recorded For All We Know at Esplanade Studios in New Orleans. You can watch a video of “Orchid Blue” from that album — and learn more about The New Orleans Collection from Newvelle Records — on the WBGO website.